“Every person has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and his family.” [1]

(Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 25)

Summary:

About 70% of public transport users rely on buses during their daily commute[2]. Yet the satisfaction of these users with its service did not exceed 12.8% and more than 86% are either dissatisfied or completely dissatisfied. Based on this data, this policy brief engages with urban public transport problems and solutions for the Greater Tunis region. The policy brief addresses 1) the problems and causes, 2) the strategic vision and possible solutions. Due to a large number of issues and their intersection with other sectors, this policy brief focuses on the problems most frequently mentioned in the reviewed reports. The proposed solutions have been generated from legislative texts and based on existing financing, digital, and physical infrastructures. Lastly, the private sector is presented as a complementary partner that can support the development and improvement of transport services.

Introduction:

Since the beginning of the 1980s, Tunisia witnessed relatively early urban growth with the state’s adoption of a liberal economic model that is based primarily on services and manufacturing industries which led to the urbanization rate reaching 67.7% by 2016[3]. This urban growth, especially in large cities such as the capital and its suburbs, was accompanied by the launch of several major infrastructure projects such as an expansion of the public bus network and the creation of the Metro network. However, the state’s encouragement of individual transportation, such as the “tax-free cars” program and fuel subsidies, has led to road congestion. Despite the public transport system’s potential to support development, weak management and control mechanisms meant it has failed to achieve its desired goals. Although the sector contributes 7% to the gross domestic product (GDP) and it employs about 120,000 workers, over the past years, the supervisory authority has been unable to make the sector a driving force for social and economic development. Instead, due to several problems, it has become a burden on taxpayers.

Problems and causes of the deterioration:

According to the Ministry of Economy, Finance and Investment’s 2016-2020 Development Plan[4] and other audit reports[5], the deterioration of the public transport system is due to several key factors, namely decreased use of the urban public transport system in the total share of transport journeys, decreased efficiency and deterioration of the transport fleet, management and administration failures, and the lack of logistical and information control mechanisms.

Decreased use of urban public transport:

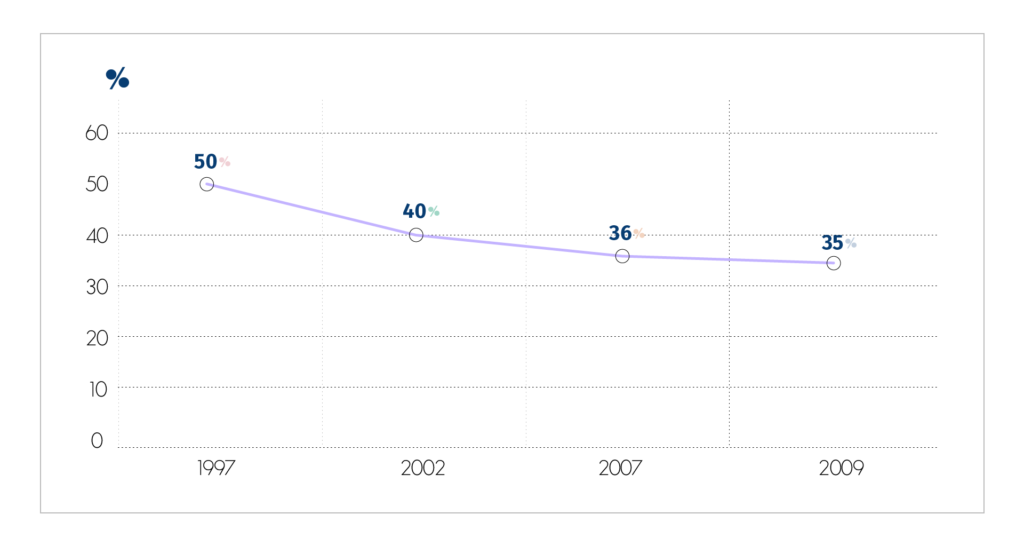

Transtu, the state-owned transport company, witnessed a significant decline in its share of the total daily transportation of bus passengers (Figure 1).[6]

This decline in usage could be explained by the improvement in the incomes of individuals living in cities (especially the wage inflation after the revolution). Additionally, the decline could be due to the availability of loans specifically buying cars through the “popular/affordable car” program and an increase in private car ownership from 27.2% in 2014 to 21% in 2004[7]. These factors, in addition to others such as poor service and lack of quality, have led to a relative decline in the sector’s income.

Despite improvements in per capita income, the dramatic increase in private car ownership has led to increased traffic within cities. The economic cost of this congestion is estimated at 3% of the gross domestic product (GDP). In addition, the country is witnessing an increase in the number of road traffic accidents compared to the global average (1,400 deaths annually), which means 1 to 2% of the GDP, according to World Bank statistics[8].

The public transport fleet’s deterioration and loss of its efficiency:

Due to a lack of demand, Tthe number of buses owned by all the transport companies decreased from 4,000 buses in 2010 to 2,900 in 2016[9] causing a lack of offer. For the public bus service to meet the expectations and needs of travelers in the Greater Tunis region, 400 operational lines are required. However, only 650 buses out of 1247 owned by Transtu are active on 240 lines[10]. This means an additional 800 buses are required. This deterioration has resulted in a chronic paralysis of the sector as the percentage of operationally available Transtu buses decreased from 87% in 2010 to 70% in 2015.

Furthermore, despite the increase in the number of passengers, from 400 million in 2007[11] to 502 million in 2015[12], the public companies in this sector continued to accumulate financial losses of 920million TND to suppliers and 820 million TND to the state’s social funds[13]. Government reports attribute this deficit to the increase in transport costs as the price of fuel has tripled in 10 years and wages increased by 44% between 2010 and 2014[14]. Also, the deficit is due to the lack of ticket price increases (the last was a 5% increase in 2010) and the large number of groups that benefit from free transport (See table below). Finally, the policy decision to increase the number of employees to more than 8000, made during the revolution to maintain social cohesion, is also adding to the deficit[15].

| Beneficiaries | Criteria for Benefiting | Percentage of Benefiting |

| Pupils and students | School transportation passes | 90% |

| People with disabilities | Special passes from the Ministry of Social Affairs | 100% |

| Journalists | Professional cards | 50% |

| Children under 3 years old | Individual/In-person Inspection | 100% |

| Children between 3 and 7 years old | Individual/In-person Inspection | 50% |

| Transport company agents and their families | Free transport passes | 100% |

| Wounded of the revolution | Free transport passes | 100% |

| Security and military forces | Professional Documents | 75 – 100% |

Table: Beneficiaries of transportation privileges [16]

Structural management and administrative deficits:

The transport sector is regulated by Organic Law 33/2004, Decree Law 2767/2004, and other subsequent laws in 2008, 2015, and 2018. This law places the sector as a national priority and regulates relations between all involved parties. Article 4 states the need to create regional authorities to regulate land transport (AROTT) to promote independence . However, no regional authority has been created for this purpose. This problem was also mentioned in the 2008 Court of Auditors report no 23 as these powers have only been created in Tunis, Sousse, and Sfax[17]. In addition, Article 9 contradicts the principle of decentralization, which is enshrined in the 2014 constitution, as it allows the governor, who is appointed by the Prime Minister, to act in place of the, so far not created, regulating authority.

Regarding the bureaucratic configuration, the network of intervening parties in the sector consists of six ministries with the Ministry of Transport (MoT) at the center. The MoT coordinates between all six ministries and is responsible for the most important tasks such as setting prices and requesting public service contracts. It also supervises all companies related to this field such as those working on technical inspection as well as road, rail, maritime, and air transport companies. Despite the magnitude of the task, the MoT allocates only 10 employees for public transport[18] and only 6 employees for inspection[19]. As indicated by the 2008 Court of Accounts report, the regional authorities rarely have designated posts for this purpose.

This led to power being concentrated in the hands of the supervisory authority and has prevented any other institution from being involved in either decision-making and planning processes. This contradicts the principle of decentralization stipulated in the Constitution of 2014. In addition, the state, represented by the MoT, assumes the various overlapping tasks of partner, observer, political decision-maker, supervisor, public relations officer, etc. which could slow down the decision-making process and take responsibility away from the Ministry-appointed board of directors. This could lead to ambiguity regarding the state’s function and could fragment and reduce oversight processes[20].

Weak oversight mechanisms and logistical deadlock:

Report N°23 of the Court of Accounts indicated poor traffic controls which cause many problems, in particular decreases in the company’s revenues[21] and it appears that traffic and surveillance and persistent problems in the sector. The report also indicated that the bus and train stations were unable to accommodate passengers and vehicles.

Although more than 10 years have passed since the report was published, the World Bank report[22] indicated that authorities have not taken any significant reform measures. However, more than one report by the auditors of the Transtu accounts identified unjustified negative differences of about two million dinars[23] for fuel between 2012 and 2015. The Court of Accounts report on energy management, which dates back to 2007[24] also included observations about the absence of a comprehensive energy audit in the transport companies. Finally, the report of the Court of Accounts mentions the failure to establish a comprehensive database. This was meant to be, along with a set of information applications, the basis for the work carried out by a national transport observatory, an institution that was not established either. The World Bank report[25] stated that one of the problems in the sector is the lack of a comprehensive IT system.

Weak oversight has led to a decline in the quality of transport and the reduction of its resources. The lack of oversight monitoring and accountability mechanisms has also resulted in an accumulative energy deficit. Furthermore, disorganized planning has led to the misuse of public space (roads). This has become an obstacle to the possibility of improving and developing the transport system, and also hinders its current functionality due to the absence of a clear policy that efficiently organizes roads in a way that considers the needs of all users (pedestrians, cyclists, and vehicles).

This has finally resulted in the quality of transportation through endless travel delays and the disastrous state of bus and train stations which lack quality standards (few seats, lack of protection and security in general).

“The magnitude of the solution matches the magnitude of the problem.”

The successive post-revolution governments have only produced arbitrary solutions, such as occasionally expanding the fleet with new and old buses or the absurd process of rejuvenating it through unnecessary redecorating operations, without adopting a clear and structured policy that is rooted in reality, to address the problems. Half of the solution is to conduct an accurate multi-stakeholder-led diagnosis, provided that this is followed up with a comprehensive strategic national vision that prioritizes the transport sector.

As discussed above, it has become imperative to establish a strategic vision and a reform policy that aims to transform the transport sector from a constrained and collapsed sector into an active contributor to the economy and a sector of environmental development in which the citizen’s interests and welfare are priorities.

The strategic vision and proposed solutions:

Establish a legislative and legal basis that is compatible with the set objectives:

In line with the constitution’s principle of decentralization, first of all, it is necessary to overhaul transport legislation (laws, decisions, and orders) towards granting regional authorities more flexibility in the management of their resources by breaking away from the current centralized bureaucracy. Then, provide all regional land transport authorities with the same powers as the Sfax (2015) and Tunisia (2018) model projects, as stipulated in the Organic Law 33/2004, thus reinforcing them with the necessary authority to mobilize all relevant regional administrations to ensure the effective performance of a sector, recognizing that the economic dynamism and social integration that will result from the reform of this sector. In this context, central and regional authorities should co-create performance-related contracts that adhere to a defined timeline which includes a comprehensive and periodic third-party audit. Also, the Assembly of the Representatives of the People of Tunisia should revise the code of Territorial and Urban Planning to determine the regional authorities’ powers at the governorate (wilaya), municipality (baladiyya), and district (mutamdiyya) levels.

Launching a digital infrastructure and the digitalization of the sector:

Although a plan has existed for more than 20 years[26], the Ministry of Transport has not yet been able to establish a road transport information system to pave the way for the establishment of a national transport observatory that provides quality assurance. The technological developments that the world has witnessed in the last decade, may facilitate the launch of modern applications and digital services to create intelligent transportation systems (IST)[27] that are connected to the Internet through an IoT network.

These systems will help improve the quality of transportation, allowing passengers to track bus locations and see estimated times of arrival. They will also help the administration to monitor fleet movements and promptly address shortcomings.

Creating sustainable financing channels for the sector:

Funding remains the biggest challenge for public projects. Negative budgets of the transport companies and budget deficits have prevented the completion of several projects and delayed others. However, the transportation sector is promising and vital and has the potential to be self-funding and even profitable. In 2015, mobility represented 10% of citizens’ daily expenditures[28]. This is considered to be a factor in the deterioration of the purchasing power of many groups in society. Therefore, the ticket pricing system must be revised to take into account the cost of transportation and maintenance on the one hand, and the economic and social pressures of Tunisian consumers on the other hand. The Farebox Recovery Ratio Index can be adopted to calculate the cost and to gradually reduce the state’s contribution by ascending this index to about 100%, and 120% in the future, so that it becomes a profitable national sector that can provide income to invest in other financially unprofitable sectors such as education and health. It is also possible to establish advanced ticket sales systems such as “Integrated Ticketing” with the use of mobile applications to reach different means of transport across the same platform and with a price standard that is appropriate for use and provides value for money.

Creating a modern infrastructure and encouraging participatory and environmentally-friendly transport:

The sector cannot evolve to meet the aspirations of travelers without the appropriate infrastructure. Creating designated bus lanes for traffic and parking is imperative for a decent urban transport system. The traffic congestion that affects roads, especially in major cities, obstructs the passage of buses and causes endless delays to their users, which affects the quality of their services. While waiting for the completion of the express railway programs (rapid rail networks), lanes exclusively for buses can be arranged. Stations must be equipped with parking spaces to avoid disruption of traffic on the roads. In this context, it is possible to study secondary roads far from the main roads and to prepare them according to their capacity for absorption. Alternative and parallel transportation are also possible solutions. Shared transportation (car sharing/ carpooling) can be legalized, and bicycle lanes with areas for safe parking can be developed near public transport stations.

Engaging the private sector and encouraging youth initiatives:

Despite adopting an economic liberalization trend since the 1980s, the state has not strictly followed this path. In the transportation sector, for example, the authorities have not issued any licenses to private transport companies since 2005, despite the numerous requests and the inability of the state-owned enterprise to meet the growing demand (only 10% of the market[29]). The private sector must be more represented in the market. To be a complimentary and active development partner, privately-owned transport companies should be encouraged to provide services for transport routes that the state-owned services do not cover. In addition, start-ups can be used to support the development of apps for public companies to boost the startups and increase national capacity in the field.

Conclusion:

Numerous workshops have been organized and many partnerships have been forged to support the transportation system in Tunisia such as workshops between the Ministry of Transport and the French Development Agency (AFD) and the German Cooperation Agency (GIZ). These workshops have produced several comprehensive reports to help advance the sector at land, sea, and air levels. These visions for reform, however, remain dependent on the completion of the express railway lines (RFR), which were supposed to be in operation by October 2020. However, despite the improvements that this would have made to the network by adding at least two lines in Manouba, the other bus lines will remain in a catastrophic state until the others are completed in accordance with the old version of the 11th development plan (namely the Al-Ghazala, Hay Al-Nasr, Bhar Azarag, and Muhammadiyah lines). Hence, it is vital to encourage the necessary political will to operationalize the report recommendations.

Recommendations:

- Initiate arrangements for the urgent review of legislation regulating the transport sector by startinged a comprehensive dialogue that brings together all stakeholders, including social organizations, to create the appropriate ground for the above-mentioned reforms.

- Launch technical consultations and requests for management proposals and control mechanisms, with successful experiences and best practices from similar economies during the development of the strategic vision for the sector, directed mainly to the Ministry of Transport.

- Launch immediate action to stop the sector from bleeding resources by initiating comprehensive auditing and auditing processes to account for and reduce losses, while strengthening the control teams and inspections with the mechanisms, expertise, and resources necessary to prepare the supervisory reports that will be among the foundations of the desired reform and structure.

References

[1] Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Available at https://www.ohchr.org/en/udhr/documents/udhr_translations/eng.pdf [2] Ministry of Trade and Handicrafts & National Institute of Consumption (2013) Research report the quality of public and private transport services for Tunisian consumers. http://inc.nat.tn/sites/default/files/document-files/Rapport%20transport%20public%20et%20priv%C3%A9%20-%20Fev%202013.pdf[3] From the 2016 Country Profile of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, p. 27. Available at https://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-documents/CountryProfiles/2017/tunisia_cp_arb.pdf[4] Development Plan 2016-2020: Volume Three: Sectoral Content: pg. 147 (issued by the Ministry of Investment, Development and International Cooperation in January 2016). Available at http://www.mdici.gov.tn/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Volume_Sectoriel.pdf[5] Reports from the websites of the relevant ministries and the reports of the supervisory Department and the oversight bodies of the Prime Minister (mentioned in the rest of the sources)[6] World Bank (2016) White paper on the transport and logistics sector. Report no. ACS18045. Transport -Middle East And North Africa (GTI05). Available at http://documents.banquemondiale.org/curated/fr/339961488471609720/pdf/ACS18045-REVISED-PUBLIC.pdf[7] Sector strategy note relating to the urban transport sector. p.11. Available at http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/843581568612862142/pdf/Tunisie-Note-de-Strategie-Sectorielle-Relative-au-Secteur-des-Transports-Urbains.pdf[8] Source 4. P6.11.[9] Source 2 [10] Source 3. P36 [11] Transport en commun dans le grand Tunis à l’horizon 2020. p.14. Lien: s http://pf-mh.uvt.rnu.tn/52/1/transport2020_tunisie.pdf [12] The Ministry of Transport’s annual project for performance capacity for the year 2019. p. 16. (Available on the Ministry’s website)[13] Arfaoui, Fadi (2020) “The first report on the conditions of transport in Tunisia”, Tunisie Telegraph. Available at https://bit.ly/3qI4BII [14] Source 8 [15] Source 4.P36 [16] World Bank. (2007) Report on the possibilities of improving public transport financing mechanisms Urban in Tunisia. Department of Sustainable Development of the Middle East and North Africa Region. p. 7. [17] Report 23 of the Court of Accounts. State supervision of the land transport sector. Report link: https://bit.ly/3lXMrPG[18] Source 4.P 30. [19] From an article on the Ultra Voice website, titled: “Shaq Shaq: Only 6 employees are in the Ministry of Transport Inspection.” Consulted on October 14, 2020. Available at : https://bit.ly/2JH5y3xreport on reform and governance of public institutions and enterprises. May 2018. “The White Paper”. P. 19. Available at : http://www.pm.gov.tn/pm/upload/fck/File/strategie-plan-action.pdf [20] Synthesis report on reform and governance of public institutions and enterprises. May 2018. “The White Paper.” P. 19. Link: http://www.pm.gov.tn/pm/upload/fck/File/strategie-plan-action.pdf [21] Source 10. P95. [22] Source 4. p.33. [23] I Watch (2017) The absence of an energy audit costs the Tunisian transport company millions of dinars. Available at https://www.iwatch.tn/ar/article/312[24] From the report 22 of the Court of Accounts “Energy Control”. Accessed Date: 10/14/2020. Available at https://bit.ly/372dLb3[25] Source 4. P 34. [26] Naciri, Maryam (2020) “Will the digitization of management in Tunisia remain just a promise?” Ultra Tunisia. Available at https://bit.ly/373wpj6[27] Intelligent transport system [28] EGIS-International and IDEACONSULT. PDNT Tunisia by 2040: Phase A – Diagnosis of the current situation – Safety of road and rail transport. Report. 2017, p.29 [29] Source 4. P.36