Introduction

So far, there is no comprehensive documentation that analyzes the Ground-Up Building Project and its key concepts, with the exception of Khalil Abbes’s book Democracy Now: An Analysis of the Kais Saied Phenomenon. This book is based on the contributions of the author, who was invited as a left-wing activist and a member of Kais Saied’s presidential campaign , to a meeting organized by Nachaz organization and Rosa Luxemburg foundation. Taking this book, as well as interviews with supporters as a starting point, while making reference to specific speeches and practices, the broad outlines of the project could be drawn.

The Ground-Up Building project emerged at the end of 2011, with the start of the first campaign to boycott the National Constituent Assembly elections. The trio Kais Saied, Ridha Chiheb El Mekki “Lenin,” and Sonia Charbti formed the first nucleus of the project, which they called “Forces of Free Tunisia” joining, therefore, the professor of constitutional law.

As Professor Ahmed Chafter points out, until 2015, several figures subsequently joined the movement, and participated in the development of the project. The period between 2014 and 2019 was decisive in terms of promoting the project via an “explanatory campaign.” This campaign was carried out in interior regions and popular neighborhoods, and its activities have multiplied in the run-up to the 2019 presidential elections to which Kais Saied, as previously agreed, presented himself.

This « explanatory campaign » is an atypical electoral campaign which goals actually go beyond the electoral framework, since it began long before the presidential elections and continues to this day. Following the promulgation of Decree No.117, Professor Ahmed Chafter refers to it, saying: “Now let’s move from explanation to application. It is through building that we free ourselves, and it is thanks to what we build that we free ourselves.” In a private interview, Khalil Abbas also said that the campaign will end as soon as the project is legally and institutionally realized. Unlike the legal and political visions of this project, its conceptual basis and its potential drifts remain under-explained. This is what this brief will attempt to clarify.

The conception of the new political regime: A ground against the institutions

This political project is based on specific points that should be introduced before being discussed. Ahmed Chafter featured some of them in an interview published by Al-Mijhar newspaper on September 24, 2021[1].

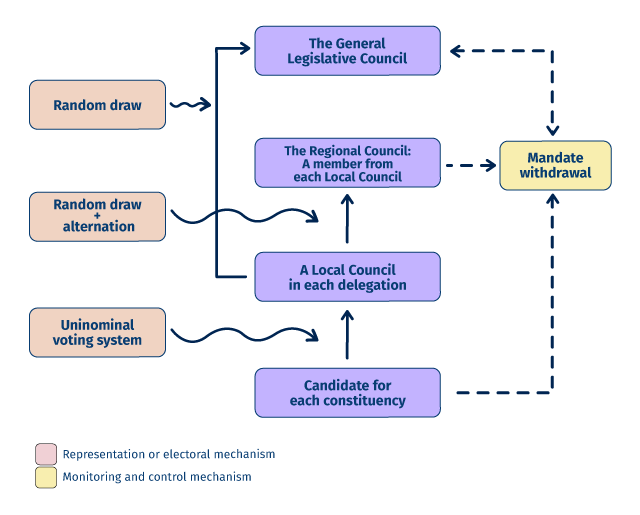

Explanatory Diagram

Electoral Law: Elections without intermediary institutions

According to this project, the revision of the electoral law constitutes one of the first major steps. It revolves around the following axes:

- Small constituencies

The project proposes the imada (the smallest sector) as an alternative to the current 27 electoral districts and as the sole voting place. There are 2074 imadas and they are spread over 264 delegations.

- The uninominal voting system

Electoral lists will be replaced by uninominal ballots in the imadas. In order to run for elections, it is mandatory to obtain sponsorship from the residents of the imada, while respecting parity between male and female voters. In addition, a quarter of the electorate must be under 35. As for Tunisians living abroad, according to the project’s supporters, the modalities of the suffrage were not specified. However, during an event in Kabaria, that took place on September 18, 2021 and that was organized by supporters of the project and the association Generation Against Marginalization, participants spoke of “open lists.”[2]

- The right to vote

Regarding this point, participation in public affairs is considered a duty; voting is compulsory and abstention may be punishable by sanctions[3]. This was mentioned by Sonia Charbti, in her speech during the Kabaria event[4], among several other proposals presented during the debate. She also indicated that blank and null votes are only allowed if they do not exceed a certain percentage. If faults occur, the election is called off.

- Election propaganda

According to Charbti, election propaganda could be banned. In addition, the parties could be present in the local councils that will be formed at the level of the delegations, since they are part of the civil society.

- Other techniques

Among the techniques added by the project we find alternation, random draw, and mandate withdrawal. These mainly contribute to reinventing and restructuring the legislative power.

Restructuring the three powers

Most revisions pertain to the legislative power. In fact, the legislative election will be eliminated and replaced by a complex process aimed at constituting a parliament called the “General Legislative Council.” The first step is to elect local councilors in the smallest territorial constituencies, the imadas. Then, one candidate per imada will be elected to join the local council. Subsequently, the remaining institutions and structures are put in place by means of the other techniques.

The members of the regional council are elected from the members of the local councils through random draw, in accordance with the 27 existing electoral districts. The members representing each local council in the regional council change and alternate, following the duration which will subsequently be specified by law.

At the same time, a random draw procedure is organized to elect a member of the local council to the general legislative council. However, at this level, the technique of alternation does not apply before the end of the term, in order to guarantee the continuity of the council’s activities[5]. The project also gives voters the possibility to revoke their vote, as a means of monitoring and supervising their representatives, under specific conditions applied by the regional or local council.

As far as regional councils are concerned, these structures mainly work to guarantee development. These councils collect and coordinate development programs that have enabled members of local councils to be successful in elections at the level of their imadas. On this basis, 27 regional development programs are collected and submitted to the General Legislative Council. Thus, the development policy of the State is determined by the project holders.

However, gray areas remain present in relation to the functions of the local and regional councils, particularly regarding the financial and logistical aspects. In addition, sectors (imadas) and delegations could be removed and replaced by regional and local councils.

The National General Legislative Council is estimated to have 292 members, 264 of whom belong to local councils, in addition to constituencies abroad. Ahmed Chafter said that the functions of the council will be aligned with the executive power, and this within the framework of the new political system which “will be neither presidential nor parliamentary.” In fact, according to him, the parliamentary and presidential systems are established according to “classic political visions which are rooted in old sorting mechanisms.”[6] As for the revocation, it will probably be dealt with in courts. As far as the presidency is concerned, direct presidential elections will take place. The President of the Republic will choose the Head of the Government who will be presented to the National Legislative Council.

A Critical reading of the political vision

According to the project, these changes will overturn the pyramid of power in order to include the citizens in the process of governance, and to respond to the demands of the people, without any party interfering with their will. By delimiting and shrinking constituencies, voters will vote for “known” individuals representing a relatively small population.

The uninominal ballot is one of the methods adopted in comparative electoral systems (Morocco and United Kingdom)[7]. Yet, this new political vision includes gray areas in relation to institutional choices and their functioning.

The hazards of a dispersed political landscape in a composite institutional framework

The individuation of the vote is one of the risks of shrinking electoral districts. In the local context, this can pave the way for cronyism, nepotism and clannism, or even give more power to lobbies and make it easier for them to attract voters.

This voting system is seen as an alternative to the list system, which had strengthened the role of political parties over the past decade. The democratic Ground-Up building project requires that each delegation has a single representative, regardless of the size of its population. The principle of representativeness (number of seats per population density) is thus replaced by total equality between the different delegations.

Concretely, this allows the interior regions to have more weight, so that they are just as represented as the most populated areas which enjoy more political and economic privileges. At first glance, this principle seems positive, but it does not prevent the same old splits and the creation of blocs in the new parliament. Furthermore, it can lead to divisions within a society that is already ravaged by a fully established regionalism.

Another issue arises regarding the local and regional structures which will be responsible for the rise to power. As local councils cannot be composed of elect-members only, it is necessary to set up a specific and permanent administration within each council. These administrations cannot carry out all types of missions within the council. It is therefore necessary to provide them with specific financial and logistical resources.

This problem also pertained to the previous assembly, particularly in relation to the possibility of recruiting permanent parliamentary assistants, given the complexity of parliamentary work. However, the fact is, this idea ultimately depends on the size and nature of the assigned missions. In addition, the presence of a local administration (in the event that a permanent administration is put in place) could lead to excesses, especially if one considers the adaptability of the phenomenon of corruption to political and legal changes.

Without regulatory frameworks, recruiting isolated individuals in new institutions can diminish the role of those very institutions and allow other powers (bureaucratic or external) to influence them. For example, this is the case of the Chinese regime where the Standing Committee within the National People’s Congress has become an effective legislative authority[8].

Moreover, with one member for each imada, the different opponents of the legislative mission cannot agree on the same political, theoretical or ideological basis, and can only be united by regional interests. These differences would cause more conflicts and therefore several crises.

The random draw, being a hazardous operation, could reverse the balance within the regional councils and thus generate conflicts. Indeed, it is possible that an elected member of the General Legislative Council belongs to a family, clan, culture, etc., that differ from the majority.

This means that the other members can decide to withdraw their mandate and block their activity within the National Legislative Council. Even by specifying the modalities of the withdrawal of vote, this can generate conflicts between the supporters of each member according to their affiliations and therefore possibly block the parliament.

Such a conception of the structure of the legislative power can lead to its dispersion and undermine its effectiveness while granting more power to the executive branch. The oldest democracies in the world face the same problem because of the expansion of the executive power at the expense of the legislative power.

For instance, it is the case with the federal system in Switzerland. Despite the country’s democratic traditions, it is not surprising that a member of the Federal Council has been in office for 25 years.Their competence and position allow them to influence the work of the Federal Assembly (Parliament), despite the great powers at the latter’s disposal[9].

This problem emerges in the new Ground-Up Building project, because restructuring the legislative power for greater representativeness (following the council system) does not mean actually strengthening it. In addition to the presidential tradition established in the society and the administration, the support enjoyed by Kais Saied suggests a strengthening of the executive power.

Exclusion of intermediary organizations and political pluralism

The legislative mission within the assembly is still to draft and promulgate laws, which means that it has not been fundamentally affected by the process of elevation. Nevertheless, this reversal introduces other actors to ensure the inclusion of the programs and visions of the interior regions. This process is limited to the “society of ordinary people” in territorially shrunk constituencies, while excluding the concept of civil society, in its modern sense, as well as its role and its institutions.

In addition, political parties cannot run for elections (although they can nominate representatives without using election propaganda). They are present in the local councils, yet without having the right to vote, just as it is the case with the organizations of the civil society. This further induces the possibility of the rise of traditionalism and conservatism. The project is based on an imprecise idea regarding the resolution of an alleged contradiction between the “ordinary” society and the civil society. While the first represents all the social, religious, clannish, tribal, sectarian and family components, the second, being a set of organizations and associations, constitutes a tool, a medium, and a space structured around values that create a balance between private and public.

Yet, the project replaces the civil society with the “ordinary” society which becomes the space where values crystallize, without tools, institutions or intermediaries, depending directly on the institutions of the political power. Added to this are the accusations leveled against civil society organizations (foreign funding, foreign intervention, etc.) and political parties, which risk being completely dismantled in the face of the next political power.

The exclusion of intermediary organizations like political parties and the civil society is a basic idea of the project, as asserted by President Kais Saied regarding the forms of political organization[10]. We expect the gradual disappearance of intermediary institutions, which explains the fact that they are not completely banned, according to what was mentioned in the draft electoral law during the aforementioned event in Kabaria.

All of this is reflected in what Ridha Chiheb El Mekki said about the political elite: “The lesson is over: it is time for the political elite… excuse me, the political catastrophe… to leave the scene and make way for a system of governance of the people, by the people, for the people and under the control of the people. Do not be offended, it is not only the choice of Tunisia, but rather a world trend[11].”

The techniques adopted in the revisions of the electoral law appear to be directed against political parties. The uninominal voting system aims to reduce their presence and minimize their supervisory role. In addition, according to Sonia Charbti’s main proposal, party members cannot run for office, and even though they are represented in local councils, they are not entitled to vote since they are not elected. Furthermore, the other techniques (alternation, random draw) only serve to distribute the members and to create structures bringing together the people who got elected according to their territorial affiliation in the different sectors. It is therefore not possible to speak of political affiliation, and of ideological positions for political parties, since the latter are considered by Kais Saied[12] as bygone forms of political organization.

Faced with a legislative power that is structured as a “depoliticized” institution, it is inconceivable for political life to be based on debate and difference. Politics is obviously not just about parties, but if parties are excluded from official institutions, they will be on the side of the opposition and the counter-power. The same goes for civil society organizations.

In its conception, the project seems to limit the possibility of politics outside the official framework. If we look at the conceptual basis of the project, the possibility of politics being free and outside the official framework seems limited. It is true that the pluralism of political parties is not synonymous with political pluralism, however, it is definitely one of its instruments. The project is based on an unrealistic assumption: the new institutions will ensure that the political authority is in perfect harmony with the will of the people. This involves merging the people with the authority, and canceling the distance that separates them.

Diminishing the role of political parties and relying on their demise is a transgression of reality and of History. In fact, globalization has led to the crisis of the State. Yet, by revealing several extremely complex problems, globalization has encouraged the intervention of the civil society and its various components to help the State mobilize the necessary skills and find solutions.

Bearing in mind the complexity of the social and economic challenges the world is facing today, it seems that the idea of sectors devoid of any form of civil and partisan organizing is a risky challenge. Moreover, in the later stages of the project, the State will be deprived of institutions that could help it cope with the problems of society. It might be true that the experience of intermediary organizations has proved ineffective for a long time, however, removing them and claiming that they are the problem, is not really a good choice.

Although they have weaknesses, these organizations are part of the historical development of modern states and modern societies; they are a guarantee of democracy and rights. A similar development has not taken place in Tunisia, but that does not mean that we have to go back to square one under the pretext of sovereignty to the people ( both conceptually and institutionally).

Human Rights

During the last period, human rights and the achievements of the Tunisian people have represented an exceptional element that is of great importance. Although guarantees have been announced by the President of the Republic, the details of the project augur well regarding potential threats, given the numerous violations observed. Social and economic problems continue to conceal the issue of rights and freedoms, even though both clusters are closely related.

At this point, it is useful to survey President Kais Saied’s vision of religion which he sees as a crucial element in relation to human rights. This is reflected in his inaugural lecture of the 2018/2019 academic year at the Faculty of Legal and Political Sciences in Tunis.

Although he is one of the defenders of Article 1 of the 1959 Constitution, Kais Saied approaches the issue of religion independently of the legal and constitutional framework. In fact, he positions it within a historical paradigm marked by internal crises and foreign interventions. According to him, the relationship with religion does not need to be framed by laws since “the issue is settled and does not require legalization or ratification[13].”

When speaking about religion, Kais Saied adopts a conservative discourse. In fact, he considers religion as an integral part of the identity of the Tunisian society. Furthermore, he separates religion from modern legislation and politics, allowing the issue to be debated within a free and open society. For example, although he says that he refuses the subjugation of an individual by another, he considers drinking or eating in public during Ramadan as provocative behavior[14].

With such a perspective, the president approaches the issue of human rights through the prism of dominant social relations. Looking at these concepts from his personal point of view, the state seems to be removed from the process of modernization. For example, regarding the death penalty, or inheritance equality, Kais Saied refers to Koranic verses to justify his refusal to revise the laws, which perpetuates the dominant traditional social representations and makes them further official.

Regarding the rights of homosexuals, the remarks made by the president are enough to reveal his vision. In an interview published by the newspaper Acharaa Al Magharibi on June 19, 2019[15], when asked about his position vis-à-vis the practice of anal testing, Kais Saied replied that the support enjoyed by minorities aims to destabilize the nation, and that it is at the very origin of the emergence of these social groups. Generally, the president relies on the context (foreign intervention, colonization, dictatorship) to justify his anti-human rights conservatism.

The new project of the democratic Ground-Up Building does not shed light on this issue and its societal impact, which is also omitted by its supporters. Only the president openly talks about it. Thus, it seems that the socio-economic aspect is the only meeting point between the positions of the president and those of the many individuals involved in the project. This can only postpone the debate around rights (especially the civil and political ones).

Professor Ferchichi asserts that Decree 117 is based on the same discrimination[16], particularly within the framework created by the consultations.

These consultations mention the laws and then the terms (which is not generally the case in legal texts). Thus, they put an emphasis on the ideas that are specific to the project, from the sovereignty of the people to the symbolism of Article 22 in which appears the date of December 17, 2010 (without mentioning January 14).

This means a total return to the period preceding the constitution of 2014 and the year 2011. Therefore, the project becomes a springboard for the economy and for society but not for civil and political rights that are left to the goodwill of the dominant social stratum while being deprived of institutional guarantees, means of development, and the possibility of future ratifications.

A weak economic vision

The technical, legal and institutional choices do not take into consideration the fact that the disparities between the regions depend both on political and electoral tools, and on the economic level. The latter is still not included in the new Ground-Up Building project. Indeed, President Kais Saied only mentioned this aspect once during an interview, when he was still a candidate. He indicated that the new economic system will be neither capitalist nor socialist[17]. As for Ridha El Mekki, his indications remain incomplete and do not provide more information on the project’s overall economic vision.

Restructuring the model of development by inverting the pyramid of power does not detract from the importance of discussing the economic model as well as the role of the state and the private sector. To this day, Kais Saied’s politics perpetuate the dominant representations. Indeed, he still positions himself in favor of the State and the social market economy (essentially capitalist representations), in exchange for great speeches that are far from being substantial.

The project of Ground-Up Building leads to the same problems that arose with the fall of the USSR and the rise of the capitalist model. Political and economic studies define capitalism as a set of multiple capitals and not as a single model, linking the political and legal frameworks to the market.

The latter is not an independent system as suggested by capitalist theories, it is rather linked to the social, cultural and political institutions that influence it and interact with it. This is what the theory of the social market economy tries to clarify. In fact, this type of economy is linked, depending on the country in which it operates, and within a single system, to the organization and supervision of social security, taxation, and services offered to families and individuals[18].

The Ground-Up Building project follows similar directions ; somehow, it does not really bring anything new. This is shown in the press release from the Ministry of Social Affairs which states: “…until a new conception of social security is proposed…” in order to enshrine equality and justice[19]. This is in line with the remarks of the president and the project’s supporters regarding economic and social rights and the way to guarantee them through legal and institutional tools allowing an equitable distribution of wealth. However, the debate does not revolve around the economic model, but rather around old ideas like social security.

Regarding the private sector, for example, President Kais Saied insisted, immediately after the measures of July 25, on the national, historical and moral responsibility of businessmen during his meeting with the President of UTICAUnion Tunisienne de l’industrie, du commerce et de l’artisanat [20]. During this conversation, he focused on market monopoly, price control and the fight against corruption. This further pushes the debate towards the political vision and its current issues, while being unrelated to any economic alternative.

The economic debate within the project revolves around economic and social rights, the development model and its reform, and the reconsideration of the margins and of those excluded from the economic cycle, through current and common concepts. However, as announced in article 22 of decree 117, he will practically be the sole responsible for this in the future, in the absence of a real participatory process. On the economic level, there have been no real dialogues with national organizations, in particular the UGTT, whose initiative has been completely ignored by the Presidency of the Republic during the last period.

The economic vision seems to suggest a break with capitalist and socialist tendencies. However, in terms of tools and concepts, it appears to be an extension of past experiences that does not differ from the capitalist reform projects that emerged in several countries after the fall of the USSR, particularly in Germany and in Eastern Europe.

These conceptions have been reviewed by the theory of the social market economy in order to integrate ethical and moral principles and thus justify the need to reduce the inequalities created by the market. This has to do with Confucian capitalism in Asia and Christian Capitalism; each of these systems has minimal ramifications[21].

In addition to the moral and ethical dimension on which Kais Saied insists (historical, religious and national responsibility, honesty and righteousness, etc.), free competition, businessmen, private property, prices, the law of supply and demand, and the role of the state in reform and control, are topics that are very present in the conceptions that are currently conveyed.

Moreover, the President of the Republic and the project’s supporters often link the economic issue to the political debate on national sovereignty and the will of the people, at an international level. The importance of these issues is indisputable. Nevertheless, Kais Saied’s interventions were ostentatious at some point, especially regarding the relationship with international organizations such as organizations of economic classification, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

These fundamental problems call for a real national unity, solidified by national institutions and economic actors, following a genuine participatory and democratic process and making it possible to avoid the seizure of power, as it has been the case since September 22. Faced with the current economic crisis, this can be seen as a way out of the current impasse pertaining to intervention and international pressure.

Conclusion

The project aims to dismantle and remove traditional institutions. Moreover, it is exaggerated to think that the new structures would serve as an alternative model to the old system, given that they are based on a complex political, legal, and technical design. The theoretical ground of the project, as well as its epistemological, cultural, legal and economic dimensions, remain incomplete and imprecise. In addition, this alternative is based on a populist vision, adopted in the name of the people and closely depending on the president, who would serve as the project’s executor. If the model is supposed to serve democracy, it remains undemocratic regarding several points, particularly its objectives.

The project raises the crucial issue of the relationship between authority and society. Even if the possibility of a return to dictatorship remains implausible, the problem arises even more with the weakening of the institutions and intermediaries of the counter-power, as well as the frameworks where the opposition is constituted, outside the institutional spaces. It is not possible to be satisfied with popular control or “spontaneous demonstrations” (an expression frequently used by the project’s supporters) to fight against all forms of deviation from the political power to be.

Recommendations

The recommendations are rather essentially centered around the country’s political transition more than the project itself. They aim to put forward objective and adequate solutions allowing the movement to the third republic to occur while preserving the recorded achievements.

At the level of the presidency

- Continue to deal with corruption cases while preventing their politicization

- Open the way to a national political, economic, and social dialogue based on a real participatory process in order to avoid the monopolization and personalization of power.

- Establish a clear roadmap to put an end to the exceptional measures of July 25th within the constitutional paradigm.

- Rely on the achievements of the democratic transition, especially in terms of human rights and individual freedoms, guarantee their preservation, and open the files of cases of violation.

- Guarantee the right to litigation and access to justice and accelerate the investigation of announced legal cases.

- Adopt a clear policy within the framework of a participatory agenda that protects Tunisia’s interests and prevents the country from getting bogged down under international pressure and from losing the support of other countries.

At the level of Civil Society and political parties

– Work to ensure that the civil society regains its central role in the political landscape, by integrating the challenges of this stage.

[1]Al-Mijhar newspaper, “The next step for Kais Saied, honoring commitments,” Tunis, September 24, 2021 (Print version).[2]Link to the page: https://cutt.ly/ZIAjE9j [3]On compulsory voting see Mohamed Ridha Ben Hammed, The founding principles of constitutional law and political regimes (Les principes fondateurs du droit constitutionnel et les régimes politiques). University Press Center, Tunis, 2010, pp.375-376. http://abdelmagidzarrouki.com/2013-05-06-14-45-36/finish/329-/66892-/0 [4] Sonia Charbti’s speech during an event organized by the association Generation Against Marginalization in Kabaria, September 22, 2021: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=546884096373519[5] Interview with candidate Kais Saied, Shems Fm, September 5, 2019: https://bit.ly/3aYKNu5[6]Al-Mijhar newspaper, “The next step for Kais Saied, honoring commitments,” Tunis, September 24, 2021 (Print version).[7] Mohamed Ridha Ben Hammed, The founding principles of constitutional law and political regimes (Les principes fondateurs du droit constitutionnel et les régimes politiques). University Press Center, Tunis, 2010, p.378.[8]Mohamed Ridha Ben Hammed, The founding principles of constitutional law and political regimes (Les principes fondateurs du droit constitutionnel et les régimes politiques). University Press Center, Tunis, 2010, p.441.[9]Mohamed Ridha Ben Hammed, The founding principles of constitutional law and political regimes (Les principes fondateurs du droit constitutionnel et les régimes politiques). University Press Center, Tunis, 2010, p.438.[10] Full interview with Kais Saied, Acharaa Al Magharibi, June 19, 2019: https://bit.ly/3DwN8IX[11]Post by Ridha Chiheb El Mekki (Lenin): https://bit.ly/3oTMz7N [12] Full interview with Kais Saied, Acharaa Al Magharibi, June 19, 2019: https://bit.ly/3DwN8IX [13]Inaugural lecture by Professor Kais Saied, Faculty of Legal and Political Sciences of Tunis, 2018/2019: https://bit.ly/3DDzHac [14]The president’s speech on the occasion of the month of Ramadan at the Zitouna Mosque: https://bit.ly/3C0hEdR [15]Full interview with Kais Saied, Acharaa Al Magharibi, June 19, 2019: https://bit.ly/3DwN8IX [16] Speech by Professor Wahid Ferchichi: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1lA_BBJRGTc [17]Kaïs Saïed: “We have to accept the rules of the game, but not the system”: https://bit.ly/3FI5msP [18] Peter Koslowski, « The social market economy and the varieties of capitalism », in Peter Koslowski (ed.), The social market economy ; Theory and ethics of the economic order, Springer, Berlin, 1998, pp.2-3. [19]Press release from the Ministry of Social Affairs: https://bit.ly/3ptN7Bw [20]Audience of Mr Samir Majoul with the President of the Republic: https://bit.ly/2Z5u0TT [21] Peter Koslowski, « The social market economy and the varieties of capitalism », in Peter Koslowski (ed.), The social market economy ; Theory and ethics of the economic order, Springer, Berlin, 1998, pp.6-8.