Summary:

Since the introduction of the 2014 constitution, governance in Tunisia has faced constant political instability and imbalance. Two rounds of parliamentary and presidential elections highlighted the political system’s dysfunction and inability to effectively govern the country. The 2014 constitution created a semi-presidential system that divides executive power between the President and the Head of Government. This policy brief argues that there is an urgent need to establish a presidential system that includes sufficient checks and balances on executive power.

Introduction

A political system is defined by the laws that divide powers and responsibilities between the branches of government. It also establishes coordination and cooperation mechanisms between the different state structures. The Tunisian Constitution determines the political system. The stability of the political system is guaranteed by Constitution article 144 which states that two-thirds of the legislature must approve any proposed amendments.

Throughout its history, Tunisia has experienced different political systems. From the Ottoman rule in the 15th century to the establishment of the French Protectorate in 1881, although the Constitution of 1861 remained in force, the Marsa and Bardo treaties stripped Tunisia of its sovereignty for the benefit of the colonizer. The Bey and the constitution were merely a façade of French colonialism.

The Tunisian Constitution of 1959 established a presidential system that granted the President of the Republic significant powers. The President appointed the Prime Minister who, under his supervision, exercised the functions of executive power. The legislative consisted of a Chamber of Deputies and a Chamber of Advisors. Due to the concentration of power in the hands of the presidency, this system turned into a dictatorial regime because it allowed the president to monopolise power and dominate all state structures thus disregarding political pluralism and peaceful transfers of power.

The Tunisian Constitution of 1959 was abolished in 2011, after the revolution, and was replaced by the law of the provisional organization of public powers pending the creation of a new constitution. This law has established a temporary system in which the Constituent Assembly played a primary role and was responsible for drafting a new constitution. Executive power was exercised in equal parts by the President of the Republic and the Head of Government; both elected by the Constituent Assembly.

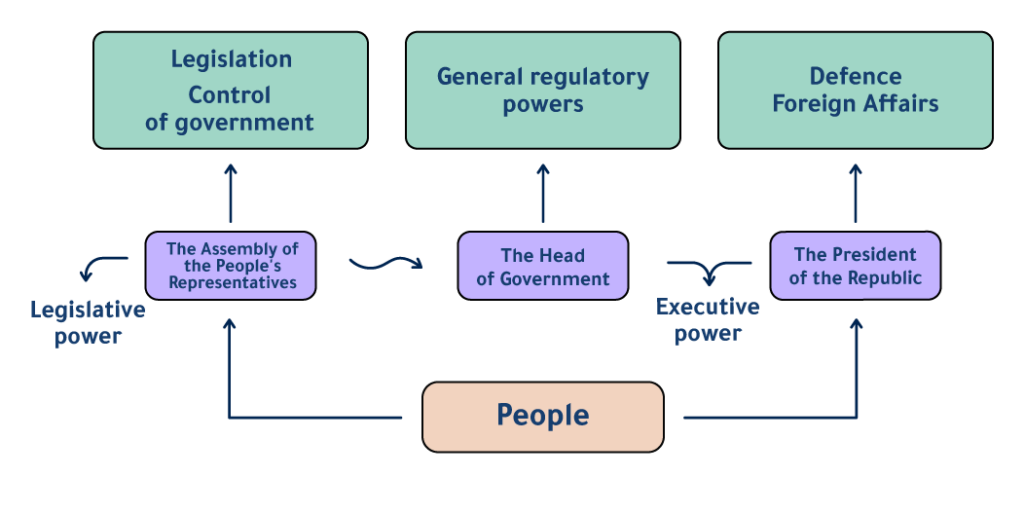

With the ratification of the 2014 Constitution, Tunisia established a semi-parliamentary[1] political system. Legislative power is exercised there by the People’s Assembly, which is directly elected by the electorate. Executive power is divided between the President Republic, who is directly elected, and the Head of Government, whose candidacy needs to obtain the confidence of the parliament.

Despite the democratic momentum of the 2014 Constitution and the establishment of a “moderate regime without the domination of the President of the Republic”[2] The country lacks political stability. Despite two turnovers of power following the articles of the constitution, Tunisia has moved from one political crisis to another. Elected municipal councils, modelled on the current regime, are also at an impasse. Akin to the People’s Assembly, municipal councils also use a party-list, proportional representation with largest remainders electoral system[3]. The municipal elections created a disjointed municipal landscape that created great tensions and led to the dissolution of 30 municipal councils in three years. The problems are the same whether it is the municipalities or the political system. In the face of such stagnation, it is urgent to revise the constitution and change the type of regime to increase the efficiency of the state apparatus.

Table 1: The different political systems in Tunisia

| Period | Constitution | Executive | Legislative | Judicial |

| Ottoman rule: 1574 to 1861 | Ottoman law | The Pasha, (representative of the Ottoman Empire | The Pacha and a privy council of janissary commanders | An Ottoman judge |

| 1861 to 1881 | Constitution of 1861 | The Pasha | The supreme council | Criminal and Civil |

| 1881 to 1959 | The treaty of Bardo and the Conventions of La Marsa | The Resident-General of France and The Tunisian Bey | The supreme council | Civil |

| 1959 to 2011 | Constitution of 1959 | The President of the Republic supported by the Prime Minister | The chamber of deputies and the Chamber of Councillors | Civil |

| 2011 to 2014 | The law of the provisional organization of public powers of 2011 | The President of the Republic and the Head of Government | The National Constituent Assembly | Civil |

| Since 2014 | Constitution of 2014 | The President of the Republic and the Head of Government | The Assembly of the People’s Representatives | Civil |

The parliamentary system: instability and inconsistency of state bodies

The Tunisian Constitution of 2014[5] established a semi-presidential, also known as a dual executive, political system that is based on a flexible separation of the three branches of government.

Legislative power is exercised by the directly elected People’s Assembly. Executive power is divided between the President of the Republic, who is directly elected after two rounds, and the Head of Government, chosen by the majority party or coalition. The People’s Assembly must approve the Head of Government’s cabinet selection and it can also withdraw trust in him/her. Judicial power falls to the financial, administrative or judicial judges under the supervision of the Superior Council of the Judges. This regime is structured so that the powers can monitor each other and coordinate. Indeed, it allows the Parliament to control the government, even to withdraw its confidence, and to put pressure on the President. The latter has the power to dissolve the assembly, in certain cases, under well-established conditions.

Although this seems defined and well-organised, this system has proven to be flawed, fostered political instability, and has caused the fall of several governments. The challenges of the current political regime are as follows:

A system that fosters political instability

The People’s Assembly, through the vote of confidence, decides whether or not to support the government. This, however, is detrimental to the executive power, as evidenced by the political instability of successive governments under the influence of upheavals in Parliament. Sometimes these disturbances provoke ministerial reshuffles and sometimes they require the establishment of a new government. As a result, the future of government can only depend on political balances within an unstable and fluctuating Assembly. The electoral system is based on a fixed party-list proportional system with largest-remainders[6] which creates a fragmented parliament. The 2019 legislative elections produced results where parties with irreconcilable differences won a similar number of seats thus making coalition formulation difficult.

It has therefore become difficult to form a government and find a parliamentary majority capable of leading and implementing its political program, in addition to internal conflicts within parties. In 2014, Nidaa Tounes won the most assembly seats (86) but very quickly, the party lost its cohesion and split into several parties. Because of these splits, the Nidaa Tounes parliamentary bloc shrunk when parliamentarians, elected on Nidaa Tounes party lists, left to establish new political parties, such as Machrouu Tounes[7] and Tahya Tounes. Afak Tounes). When parties participate in elections and subsequently lose their cohesion, it results in a greater dispersion of seats. This makes forming a majority coalition in Parliament more difficult.

Political instability is also caused by the creation of new parties in the Assembly whose members won their seats on other party lists. They are the result of either party splits or the gathering of independent representatives. Such is the case of Tahya Tounes who, although he did not participate in the legislative elections of 2014, was represented by 43 deputies in the fifth parliamentary session 2018-2019. The fragmentation and instability that plague the parliamentary scene is due to the absence of strong and structured parties with a stable political base. Apart from Ennahdha, who has participated in every election since 2011 and has managed to preserve his bloc in the Assembly, most parties during the 2014-2019 period fragmented either during the term of office or between elections.

Independent MPs and unorganised political movements (such as coalitions, independent lists and new forms of political organisation) now play an important role. Because they are difficult to categorise according to traditional political classifications and they are characterised by their incessant fluctuations, constantly modifying their alliances and complicating the situation even more.

Figure 1: Partisan tourism during the 2014-2019 parliamentary term[8]

Due to the link between the Assembly and the formation of government, political turbulence and dispersions within Parliament impacted the executive power, which has been affected by the configuration of political alliances in the Parliament. The political instability thus ended up reaching the government. Political instability stems from the overall political situation in the country concerning parties and their agreements. Political stability is linked to that of the government by virtue of its existence and its capacity to implement its public policy. The instability is evidenced by the continuing crises of government formation and ministerial reshuffles. In the current political system, the formation of the government passes by its preliminary nomination by the party which won the elections and then by a vote of confidence from the assembly. The parties in the Assembly are forced to find a consensus. Partisan quotas and bartering are required for the government to get parliamentary approval.

Since the implementation of the new constitution, government crises have followed one another, especially after the 2019 elections. Habib Jemli was initially appointed, by Ennahdha, to set up a new government but his proposed cabinet list did not receive the majority support, because of the disparities caused by the results of the elections. This caused a waste of time for the country as it remained under the authority of the interim government of Youssef Chahed for two months. This delay was not without consequences, given that the new composition only took office two days before the discovery of the first case of infection with the Coronavirus. Thus, the country could not prepare to face the health crisis. Even if they managed to form a government, the latter would be strongly affected by the changes in the political balance within the Assembly.

The fickleness of political forces sometimes leads to the overthrow of governments. This was the case with the government of Habib Essid, against which the parliament passed a motion of censure under the Carthage Accord, but also with the government of Elyes Fakhfakh. The fall of the latter is a telling example of the impact that political instability in Parliament can have. The product of political coercion, this government was already doomed and its aim was to “widen the political belt”. Moreover, while the government escapes the threat of overthrow, it is nonetheless compelled to implement cabinet reshuffles. Indeed, the impact of the split of Nidaa Tounes within the parliament can be seen in the ministerial reshuffle carried out by Youssef Chahed and which led to the dismissal of the ministers of Nidaa Tounes and their replacement by members of Ennahdha and of independents rallied to his party. The same scenario was repeated with the government of Hichem Mechichi, which very quickly effected a reshuffle, a few months after a vote of confidence. Almost a third of the government was dismissed but tensions between the Prime Minister and the President over this reshuffle blocked the process[9].

For the last 6 years, the country followed a cycle of negotiations around the formation of governments, their overthrow, or their reshuffle. It is therefore not surprising that since 2014 there has been four prime ministers and six different governments were formed at the rate of one government per year. Some ministries have seen a large number of ministers in a short time. The instability of the government results in the disruption of public policies and national strategies at a time when the country needs stability and coordination between its various bodies. With the pre-existing challenges, it is difficult for the composition of a coalition government to gain the confidence of parliament and respond to the various political sensitivities that exist within it.

Disputes within the executive

The Tunisian Constitution of 2014 divided executive power between the President and the Head of Government. The President has relatively limited power compared to the Head of Government. The President is responsible for foreign policy, defence, national security and can make appointments to certain important state roles. He/she also has the power to propose new laws (legislative initiative) in certain areas defined by the Constitution. All other executive responsibilities fall to the Head of Government[10].

The Constitution also establishes a set of mechanisms that allows the two heads of the executive to interact, in particular regarding the possibility for the President to chair ministerial councils. The two must coordinate in the appointment of a foreign minister and the head of government must attend meetings of the Supreme National Security Council. These mechanisms serve to ensure the two parties coordinate.

However, the periods after both the 2014 and the 2019 elections have proven to have practical limitations of this system. In the absence of a harmonious relationship between the two positions, the executive power is divided, especially since it is part of an unstable political environment for years.

Tensions between the two heads of the executive began to emerge during the heated dispute between Prime Minister Hamadi Jebali and President, Moncef Marzouki, over the extradition of former Libyan Prime Minister Baghdadi Ali al-Mahmoudi. Even before the 2014 constitution was finalised, the executive power was already showing signs of division.

In the political arena, conflicts continue to multiply. After the 2014 elections, the former President, Beji Caid Essebsi quickly sacked the head of government Habib Essid after appointing him himself. His successor, Youssef Chahed, had extremely strained relations with the president until his death. Following the 2019 elections, and while President-elect Kais Saied had a relatively good relationship with Prime Minister Elyes Fakhfakh, the same was not true with his successor, Hichem Mechichi. These tensions peaked at such a level that the latter prohibited his ministers from meeting with the president without his approval. For his part, he hampered the swearing-in of new ministers. In addition, he repeatedly criticised the government’s performance. Therefore, the distribution of executive power between two conflicting parties can only obstruct the political functions and weaken the performance of state institutions.

Regarding foreign affairs, the Tunisian constitution grants the President wide powers. However, without coordination with the government, managing foreign relations or signing agreements is almost impossible. This explains the difficulties encountered in importing vaccines during the health crisis and the blocking of many agreements whose application requires government approval. As on his visit to Libya, the President went there alone before the Prime Minister also paid a visit. The issues discussed differed each time and the situation repeated itself in other cases of diplomatic demarches at the international level. By attributing the quality of “Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces” to the President, the constitution does not explicitly specify whether these forces are civilian or military. This ambiguity has caused disagreements between the two parts of the executive branch and further confusion in the leadership of the security forces, especially when directives clash. In many cases, the roles overlap, disrupting the workings of the state and harming the interests of the country. This has created tensions within administrations and executive structures and weakened their effectiveness. The management of the Covid-19 health crisis illustrates in many ways the danger presented by this divided executive. Indeed, the state apparatuses have come up against the lack of cohesion and coordination between the Head of Government and the President at the decision-making level. The situation in the country has therefore deteriorated on all fronts.

A system that promotes political irresponsibility

In the Tunisian political system, there are separate legislative and executive elections. The voter chooses a party-list for the People’s Assembly and a presidential candidate in the executive elections. The head of government is not directly elected. Instead, he/she is selected by the parliament granting him/her, and his/her cabinet, confidence.

This system has several contradictions. For example, the president, who represents half of the executive branch, is elected via two rounds by direct election and derives his/her legitimacy from the people. However, he/she does not have as much power as the Head of Government, who is not directly elected. But above all, this system does not encourage parties to take responsibility. The post-2014 period has shown that the parties that win a plurality of seats in the elections are permitted to appoint a prime minister, but chose to hide behind the non-partisan and independent figures.

In some cases, the people who were unsuccessful in the elections become part of the government, resulting in the emergence of governments that lack electoral legitimacy. This is evidenced by the case of Prime Minister Elyes Fakhfakh. In the 2019 legislative elections, his party, Democratic Forum for Labour and Liberties (Ettakatol) did not win any seats in the Assembly, but he became the head of the government[11].

The principle of elections and the spirit of democracy presuppose that the person elected is judged at the end of his term of office. However, the parties are avoiding responsibility on the pretext that the government is either independent or part of a coalition. An election also requires candidates to be appointed based on a political project and program. However, because of consensus, parties that won seats in parliament quickly abandoned the political programs they promised their constituents to develop completely different new projects. In some cases, voters elect one party to disqualify another without considering the possibility that the two parties could ally themselves, with consequences contrary to their expectations.

The Tunisian constitution and electoral law provide no means of revoking or withdrawing confidence from members of the Assembly, regardless of any mistakes made because MPs enjoy parliamentary immunity and their mandate cannot be shortened. The flaws in the current political system allow MPs to avoid responsibilities with impunity. On the other hand, the President, who is directly elected, takes responsibility for failures and recovers the credit for successes, the voter has chosen him/her rather than his/her party. Elections, therefore, offer the means to punish an elected official by not re-electing him/her.

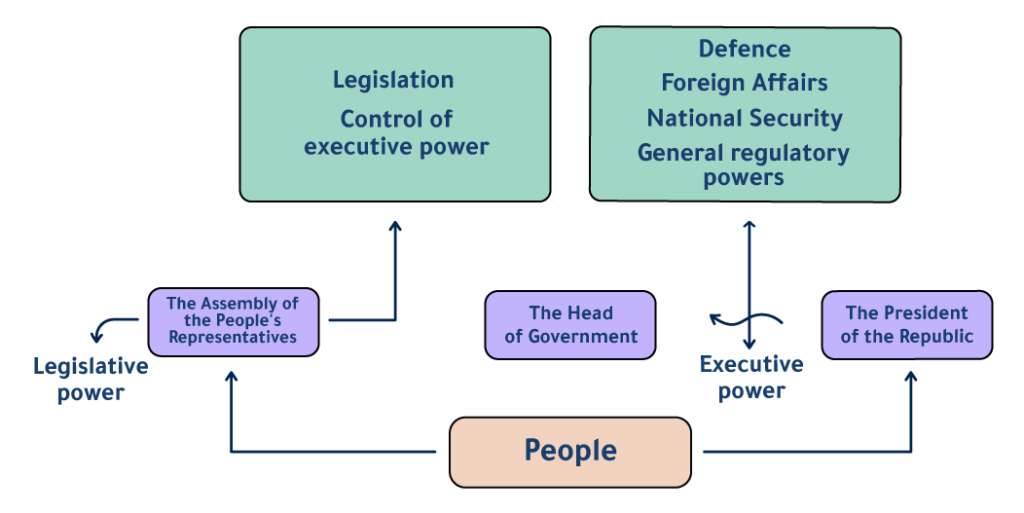

A presidential system is a more effective model

This is not to say that the parliament should be abolished but more powers should be transferred to the Presidency. This system would not differ from the Constitution of 1959 but would include sufficient checks and balances to ensure that the system does not deviate towards a presidential dictatorship.

A presidential system guarantees coordination of state bodies

The current system has weakened state institutions’ effectiveness because executive power is divided and the two leaders have consistently had a conflictual relationship. It is necessary to implement a system where executive power is aggregated; a presidential system. The President, directly elected after two rounds, should have the authority to appoint a head of government who operates consultation and coordination with the President. The President can dismiss the HoG and supervise the Council of Ministers. This model makes it possible to unify the executive power so that public policies are controlled by a single body. Coordination, therefore, becomes possible and sustainable. In addition to creating decisional harmony at the national and international level to implement them and avoid political crises.

The implementation of a presidential system does not reduce the importance of the Parliament’s legislative power. This system must include mechanisms to promote cooperation between the President and Parliament, particularly within the legislative framework. For example, any law put in place by one requires the approval of the other. The same must be applied to the annual budget, international agreements, and declarations of wars or sending military forces abroad. In addition, each party has leverage to ensure a balance of power. The assembly must also have the power to dismiss the president in the event of a serious violation of the Constitution, in particular through the Constitutional Court. In return, the President should, in certain cases, have the power to dissolve the parliament. This model also offers other mechanisms of interaction. For example, it allows the President to address the Parliament, just as it guarantees the latter the possibility of questioning the government, the Prime Minister, and the President. These are all means that promote coordination between state apparatuses and ensure a separation of powers.

Delegate political responsibility

In a presidential system, the President is directly elected to exercise executive power. Elections retain their value since the President has broad powers which facilitate the implementation of his/her electoral program. This makes avoiding political responsibility no longer possible. Consequently, the President assumes political responsibility for failures either through electoral punishment, i.e. not being re-elected, or through other mechanisms such as withdrawal of confidence by the Parliament, which takes the necessary measures for dismissal. Thus, the President is accountable before the electorate and respects electoral legitimacy.

Guarantees against the abuses of the presidential system

Tunisia is suffering from the traumas of the despotic presidential regimes of Habib Bourguiba and Ben Ali who dominated all state institutions. These experiences fuel fears of a return to dictatorship. However, not all presidential systems are dictatorial, and not all parliamentary systems are necessarily democratic. However, it is possible to emulate a model that upholds all the components of a democratic system. The United States’ system is an ideal example because while the President exercises executive power, Congress, the bi-cameral legislative, is an active force with great political weight.

It is therefore a question of implanting a presidential system with sufficient legal guarantees to prevent potential drifts towards a dictatorial regime, such as creating constitutional institutions which strengthen democracy and preserve the independence of the judiciary and freedom of the media. But it is above all the mechanisms available to Parliament that guarantee democracy.

The Assembly must be able to follow and supervise the executive power to hold it accountable. For example, it may refuse to adopt laws and even dismiss the President o. Thus, the presence of a strong functional Parliament helps maintain democracy in a presidential system. In addition, the current constitution, by specifying the duration of mandates, offers another guarantee. By law, the President is only entitled to two consecutive or separate terms and cannot amend the Constitution to extend that term[12]. This chapter is considered to be an important achievement and the modification of which requires the complete revision of the Constitution, given the complexity of the constitution-making process. Therefore, it ensures the peaceful transfer of power and prevents the monopolisation of power in the political system.

Recommendations

At Presidency level:

- Organise a national dialogue around the constitutional revision project that includes a balance of all political parties and public institutions, especially those representing women and young people.

- Revise the chapter relating to the executive and legislative powers and reformulate it in accordance with the principles of a presidential system, review and modify the rest of the chapters to make them compatible, provided that any amendments do not affect any rights or freedoms acquired under the 2014 constitution.

At the Legislative and the Presidency levels:

- Establish a Constitutional Court in parallel with the revision of the Constitution.

- Organise early presidential and legislative elections in accordance with the provisions of the new Constitution.

[1] Choudhry, Sujit and Stacey, Richard, Semi-Presidentialism as a Form of Government: Lessons for Tunisia (2013). International IDEA & The Center for Constitutional Transitions at NYU Law Working Papers: Consolidating the Arab Spring – Constitutional Transition in Egypt and Tunisia (with R. Stacey) (2013), Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3025975 [2] Ridha Ben Hammed, The constitution of the Tunisian Republic of 2014 and the democratic transition. work in tribute to Dean Salah Ben Aissa, Presses du centre universitaire, p.9.[3]See organic law no 2014-16 of May 26, 2014 relating to elections and referendums for further details. [4]Shems FM, Dissolution of 30 municipal councils in three years. https://bit.ly/36U1oNC [5] https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Tunisia_2014.pdf [6] Marsad – Simulating 2011 election results. https://anc.majles.marsad.tn/simulation_modes_scrutin [7] Business News (2016) Mohsen Marzouk announces the name of his party. https://www.businessnews.com.tn/mohsen-marzouk-annonce-le-nom-de-son-parti,520,62849,3 [8]Al Bawsala, Marsad Majles, The 1st parliamentary term in figures (November 2014 – August 2019), p.10. https://www.albawsala.com/ar/publications/20193271[9]Shems FM (2021) The Parliament gives Hichem Mechich’s government a vote of confidence. https://bit.ly/3Bg0w3M [10] See Articles 77 and 78. https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Tunisia_2014.pdf[11]Middle East Monitor (2020) Tunisia’s parliament approves a coalition government https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20200227-tunisias-parliament-approves-a-coalition-government/ [12] See Article 75. https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Tunisia_2014.pdf